Dual-Coding Theory

100 years ago in a galaxy not so far away, humans discovered that remembering images is easier and faster than remembering text. Despite this fact, billions of online accounts are guarded by strings of letters. To make matters worse, we are constantly advised to choose unique, long, and random character strings that are impossible to remember, one for each of our online accounts. Twenty years ago, researchers showed that more than 27% of people forget their passwords regularly and more than 81% of people forget one or more of their online passwords at least once. There’s no doubt that the numbers are higher today. At Valt, your master password consists of images—not characters—and we use the principles of dual-coding theory to help you remember it.

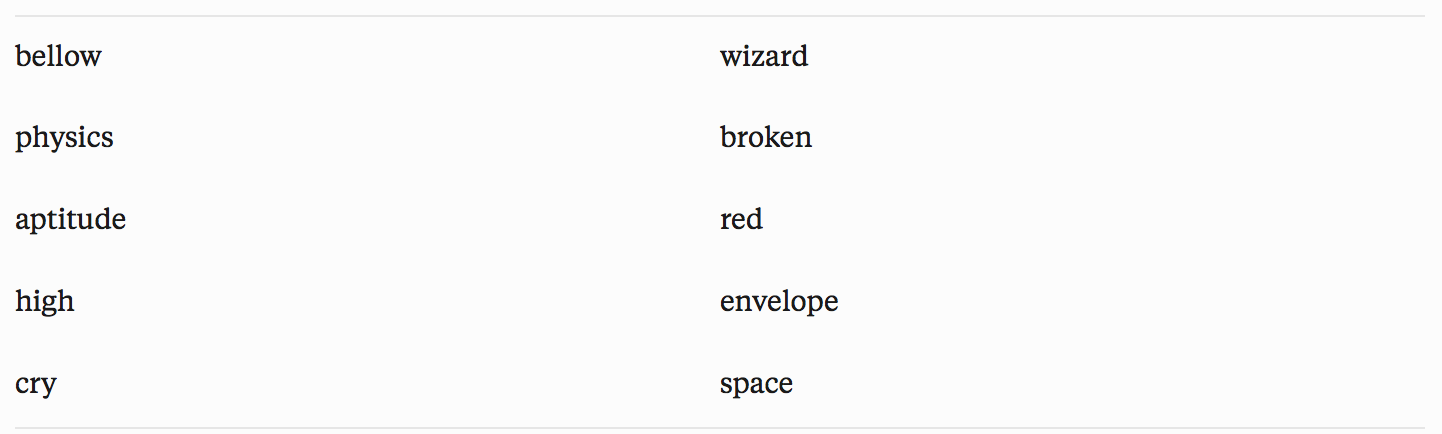

The dual-coding theory, introduced by Allan Paivio in 1972, highlights how people commit things to memory using both verbal and visual information. People are more likely to recall information in the future if they are exposed to both text and images that complement each other. Try testing yourself right now. Read through the first list of words in the first footnote1 for a few seconds, then go on to the next paragraph.

(Okay, no more looking at the words. We’ll come back to them in a minute.)

When Valt trains you to remember your master password, we show you a sequence of images and teach you fun facts about what you’re seeing. Somewhat counterintuitively, learning all that extra information makes it easier to remember the images. When you are exposed to multiple information formats, your brain forms a web of connections between neurons. When the web becomes large enough, it’s easy to remember the bits in the center because there are many paths available to reach that information.

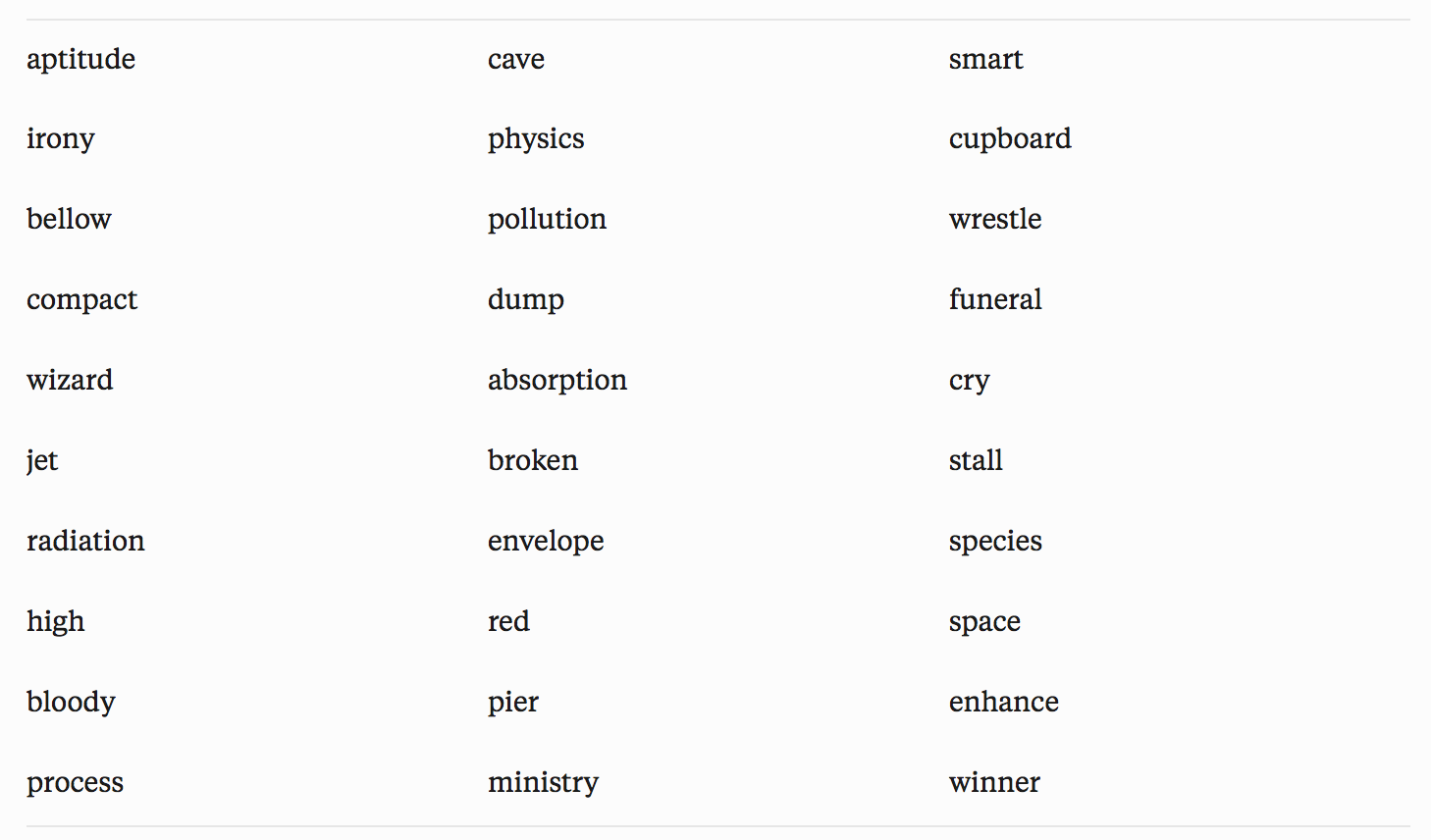

Let’s see what you remember. Take out a sticky note, then examine the table below to see which words you remember from the footnote, writing them down as you go.

Now check your work with the words in the first footnote1. How many of the original ten words did you find? This kind of memory task is called recognition because we gave you options from which to pick. When you unlock your Valt, you’re leveraging your recognition memory to pick your images from a grid of red herrings. You can read more about recognition memory on our blog. Typical passwords use recall memory tasks instead which require you to reproduce your password without any prompting. According to Dr. Edith Mulhall, the average person can learn to accurately recognize images 4.6x times faster than they can learn to accurately recall words.

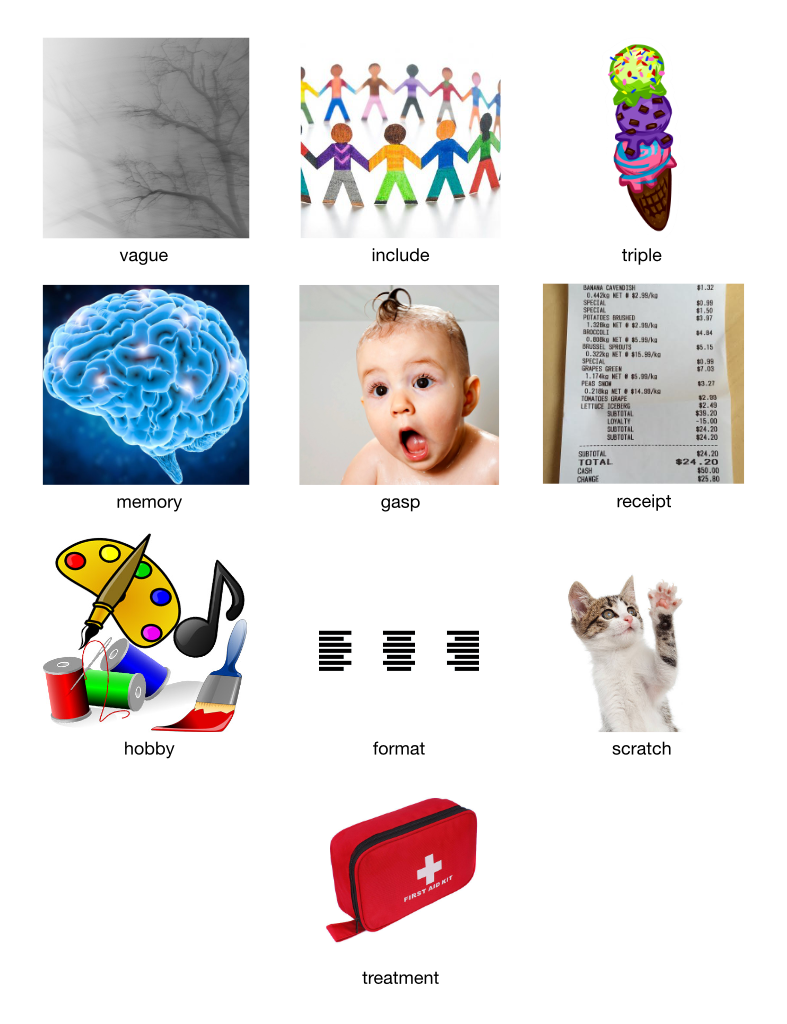

Let’s see how you do memorizing information with the power of dual-coding theory on your side. View the words and images in the footnote table2 for a few seconds, then go on to the next paragraph.

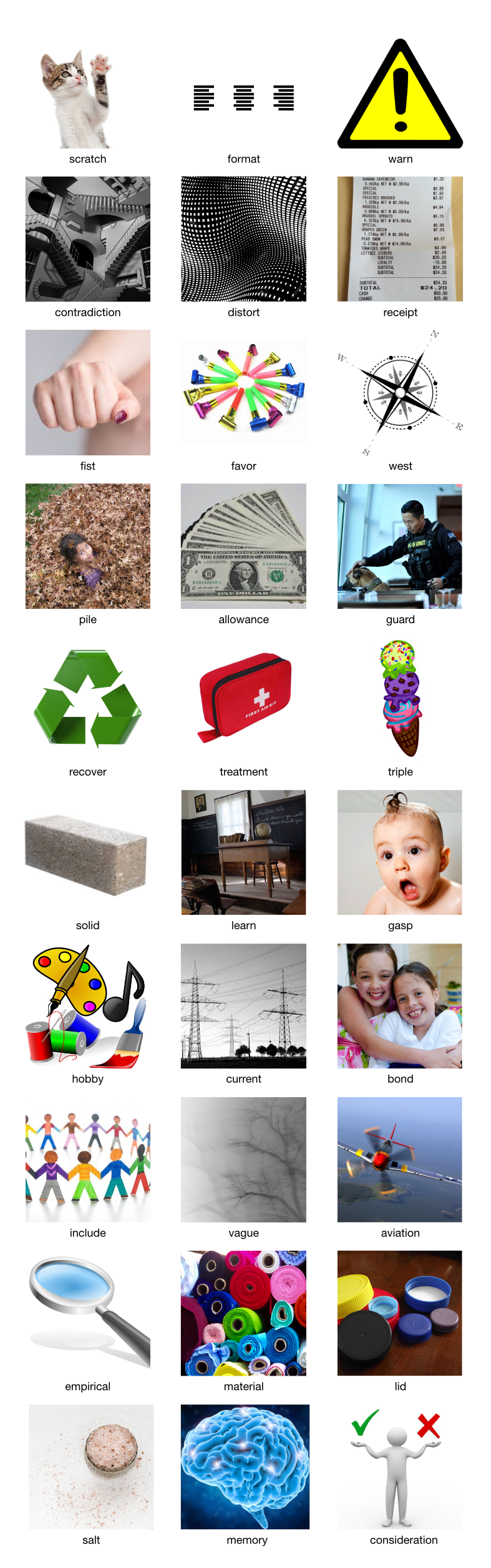

Valt takes dual-coding theory and ramps it up to quad-coding theory: textual, visual, spatio-temporal, and muscular memory. Every time you select your images from the grid, they are presented in the same arrangement and the same order. This property builds up your spatio-temporal memory. When you use your fingers to select your images in the same pattern each time, you also bolster your muscle memory. Eventually, you’ll probably be able to enter your images with your eyes closed. It’s time to test the dual-coding theory. Look through the grid of images and text below, writing down the words you recognize on a handy dandy sticky note.

Now check your work again in the footnote.2 How’d you do? Unlike the images for this test, our Valt grids have been deliberately curated for beauty and memorability. In case you want to read more about how we do that, we’ve dedicated a whole blog entry to describing what makes an image memorable. Committing your password to memory via our scientifically-proven training techniques significantly increases your chances of remembering your master code. These facts are not wacky new ideas; they’ve been around for a century–yet the world of cybersecurity has been slow to catch on.

Time to play catch up.